UNITY ENGINE

TOOLS

MACHINATIONS

MIRO

FIGMA

ATLASSIAN SUITE

GOOGLE SUITE

ARTICY

Aether, iron, blood, sweat and story

Aether and Iron is where I was able to hone my collaborative writing and narrative structuring skills. On this project, I had the ability to create proposals for narrative architecture and put forward restructuring scaffolds that reframed the way we designed player choice and agency.

Additionally, I contributed to game economics and combat design — who said flying cars can’t be affected stop signs?

♦ Key Roles ♦

♦ Performed functionality testing, smoke testing, regression testing and UX testing

♦ Collaborated with designers to create gameplay experiences within larger systems e.g. utility items, status effects

♦ Created scaffolding plans alongside production to improve communication between external and internal teams

♦ Improved user experiences by communicating design issues with design teams

♦ Outcomes ♦

♦ Learned how to communicate calmly in high pressure situations with a deadline - you can do as much as you possibly can in one day, and that’s okay

♦ Developed communication and presentation skills to be appropriate and professional for external clientele

♦ Honed inter-departmental collaborative skills, being aware of costs to department outside of my own. Improved at requesting information from designers to work efficiently in existing systems

♦ Challenges ♦

♦ Worked in high pressure sprints of 2 weeks, with each decision being the right way forward, rather than for maximum output

♦ Had to learn to create content in a way that would reflect positively to clients

♦ Professionally developed into narrative design, having to learn how to look outward from my own department and think about the implications to development, art and production

♦ GAMEPLAY IMAGES ♦

♦ NARRATIVE DESIGN ♦

CLASS OF CHOICE

Summary

We needed a structure that defined the priority of choices to the narrative. Based on a talk by Daisuke Iwasaki, I developed a categorical system that defines ‘choice types’ that suited the needs of the project. The idea is that each quest encapsulates a set number of choice types (based on severity to the narrative) to better balance content in the greater story.

Execution

These categories helped define a few key points in the narrative system.

It gave writers a clear indication as to how many of each choice were in different quest lines. This also indicated to the writers and design team a numeric value to balance narrative beats across a long story.

It created numerical data to allow designers to reflect on content available in each quest.

It clearly scaffolded and created points of comparison to where some quests were lacking content, and where quests had too much content.

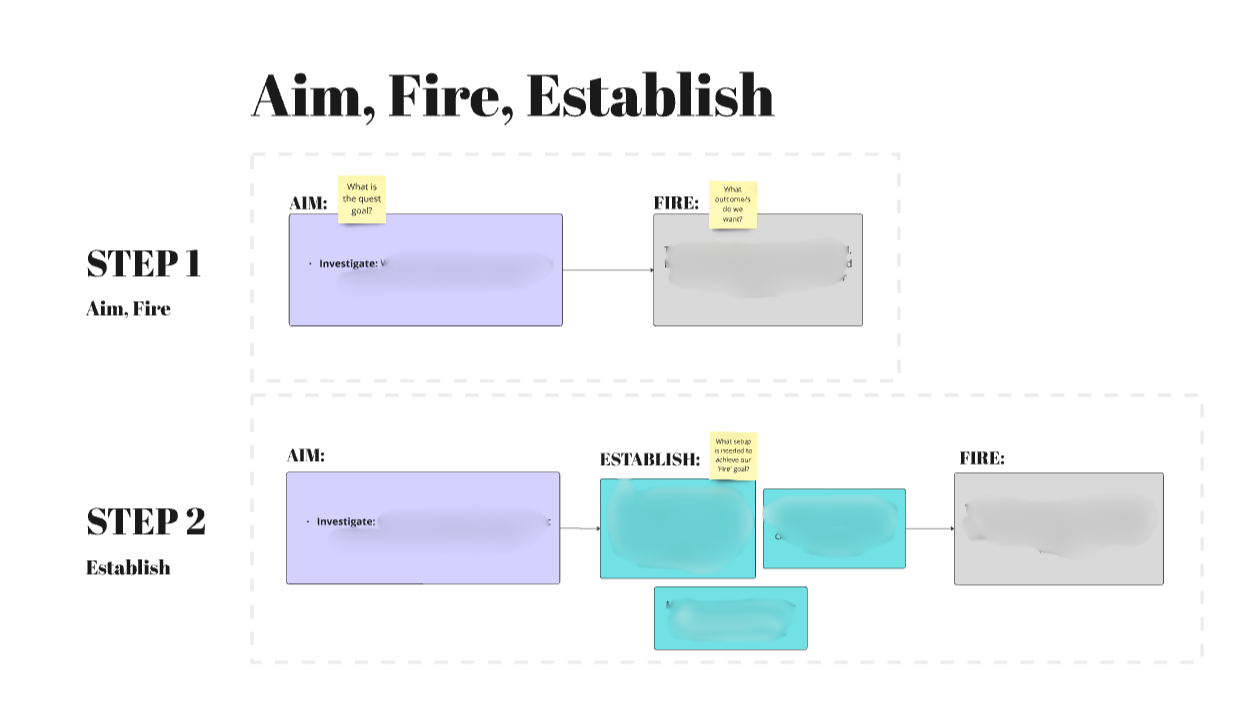

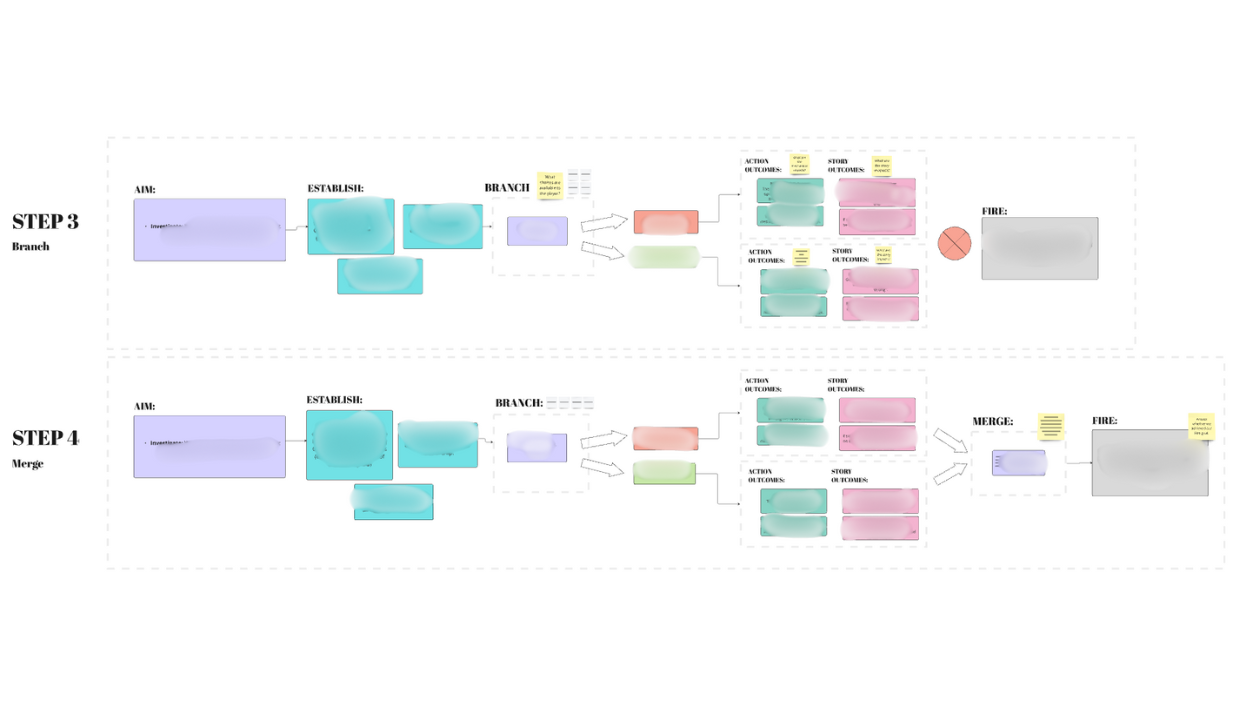

AIM, FIRE, ESTABLISH

Version 2

Version Final

4 PATHS FORWARD

Summary

More or less a theory/argument I formulated for the importance of having 4+ choices to create a true sense of player agency. This came to me when I dreamt of Aristotle and then slack called my producer the next day screaming the number 4. This is at the end of the narrative design section for obvious reasons.

Execution

Breaking down ‘choice’ can be made incredibly easy and formulaic. There are an incredible amount of instances in RPG’s where choice ‘types’ are broken down into the four temperaments:

The Walking Dead (Example to the right)

“Gone, but won’t come back” (Phlegmatic)

“…” (Melancholic)

“There’s nothing to say” (Choleric)

“There was no time for a burial” (Sanguine)

This was more of a design ‘theory’ based on psychological studies, if you’d like a better picture of the madness, here was version 1 of the work I did for this:

Summary

A problem my producer and I sought to solve was how quests and storylines felt disjointed from game features due to the distance between narrative and development teams. By creating a scaffold for writers to pre-plan story and action levels, the Aim, Fire and Establish framework brought together ludic gameplay and emotional beats in a neat, legible diagram before pens hit the page.

Execution

It informs development of possible implementations or features required by the narrative team to further the desired story.

It allows production and the writing team to spot or preempt plot holes or jumps in logic from a player perspective. It puts development closer to the player experience by listing out both the gameplay and emotional story beats.

It allows writers’ to utilize available features, or design and think of new features before putting time costs on development to prototype.

It provides a mechanically and emotionally clear structure for writers to write to, eliminating large chunks of rewriting and revision costs.

Version 1

♦ SYSTEM & COMBAT DESIGN ♦

Design Idea Pipeline

Unfortunately what I designed is under NDA (a simultaneous sigh rings out through the industry), so the best I can do is describe the pipeline my senior designer gave to me to get ideas through the door and in front of production + the client.

Step 1: A problem

As design problems manifested, I learned valuable lessons from my senior designer. Whilst I was quick to jump to glorious ideas of redesigning systems as a whole, my senior designer forced me to sit back, and think about what the real problem was by analysing and collecting trends of feedback from external playtests. He also encouraged me to clearly think about how I presented the problem to production:

Does my solution conflict with client goals? With game pillars? What is the cost of exploring ideas, and how can I convince production that this is worth the time? What do I actually want the outcome to achieve for players.

A broad example, and broad so I don’t get sued, is that combat wasn’t ‘fun’. My initial response was: “why don’t we rework X system to allow players to interact with something in every round?”. What I failed to ask is “what makes it not fun, and why?”. Sometimes the solution to a problem is not an answer, but another question. If I had to ask “why is it not fun?” then there was obviously a disconnect between my interaction with combat versus. the players.

Once I could identify a problem and answer all these questions with real data behind them, then I could move on.

Step 2: Design Proposal

The Design Proposal document forced me to think about the greater impact my design had on existing systems. It also allowed me to workshop the protentional labour costs of development if this proposal went through, and reflect on the idea not only as an implementation, but as a project cost. This document made me think about why I’m proposing this idea, how it’s a unique selling point compared to competitors, and how it interacts with existing combat mechanics.

Step 3: Paper Prototype

The next stage was paper prototyping the idea to put in front of a few co-workers and validate ideas. Creating a quick paper prototype was a low cost and low time consuming method to quickly proving to myself what parts of my idea worked, didn’t work, or had potential edge cases that other people could see, that I could not. I created some very simple cards and tooltips on google sheets, printed them out and organised it like a boardgame.

Step 4: Turmoil

A part of the design process that is often overlooked, but always instilled into me by my senior designer: always prepare to let go of your ideas, or have them crushed by production. Whilst my idea in this scenario was one of the rare ones that was liked and enjoyed by most of the team, I was able to receive critical feedback to refine the idea, and balance the prototype economy before proposing this to production.

Step 5: Pitch to Production (or senior designer)

The large selling point of this idea was how it tied into systems we had already developed. In refining the idea and learning the lessons I had in step 1, I presented this idea to production with a simple prompt “this solves X problem by…” and had a fallback going “this will only expand our existing systems…”

In the end my idea got scrapped because of combat reworks but hey, that’s the game designer life. :)

♦ SOLVERS ♦

Let’s mathematics english

Based on a Yarn Spinner talk I saw at Games Connect Pacific Asia, I began to think about applying mathematic formulas to writing. This talk was phenomenal in explaining the concept of breaking down RPG narratives into simple solutions (or solvers) where a program could calculate possible and impossible outcomes when values are attributed to player choices. If you are a narrative person reading this, and are confused, I feel you. Here’s a diagram I made to explain this to myself as I began short-circuiting:

Solvers basically take values attributed to story beats e.g. Going to the blacksmith = circle, and can calculate possibilities and impossibilities like a maths equation.

In the solver above which I was working on, it’s basically solving whether you can reach star by solving story beats like a simultaneous equation. Hopefully that made sense, sweats.